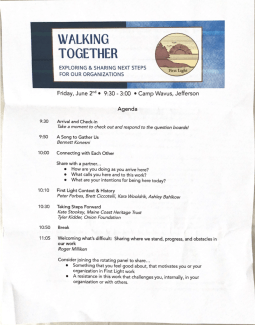

As I share words from this event, I want to thank everyone who contributed to it. The agenda is included here, though there were many who are not named and who shared powerful thoughts. It’s a challenge to recreate words shared with passion, vulnerability, and heart and I acknowledge that some of what was shared was deeply personal. I’ve tried to generalize what was spoken as best I can, particularly the unscripted words. Apologies for any omissions or oversights.

Photo by Peter Forbes

Event agenda page 2. Image by Ashley Bahlkow.

Even before seeing familiar faces and receiving warm greetings at the main lodge, I already had gravel in my sandals and gritty toes from the walk from the parking lot. Like many others, I entered the high-ceilinged, timber-framed gathering space in office clothes, as I would any such professional gathering of this kind. But by 10:00 with Bennett Konesni’s first song, where my voice disappeared into unison with almost 100 others, I felt like I was becoming more authentic, more deeply human, and more connected to those around me with the bounds of professionalism waning.

Throughout the day, there were smiles and tears. There were inspiring speeches. Perhaps most impactful for me were the earnest voices from those not on the agenda who shared their challenges and learnings–both organizational and personal–unscripted. First Light catalyst and event leader, Ellie Oldach, cultivated a space of vulnerability and authenticity–two amendments for sprouting the seeds of deep-rooted relationships. One thing was clear for me on this day: we are not alone in this work. We are growing together. And, most importantly, there is space for more. In fact, multiplying the numbers of us doing this work is absolutely essential to Wabanaki land return, sovereignty, and justice.

Photo by Peter Forbes.

We started by pair-sharing. I was inspired by Louise Jensen’s words from the Maine Appalachian Trail Land Trust, who expressed her excitement to reinvigorate and refocus their board on land justice learning.

Longstanding First Light catalyst Peter Forbes then spoke inspirational words into the room, reminding us, “We are coming late to the game but we are here now.” He reminded us of our commitments to this work towards Wabanaki sovereignty and the importance of supporting each other and holding each other accountable–essentially how we move together–the theme of the gathering. Peter encouraged us to put shared values over our organizational identities, to change the sector’s narratives, and especially to reimagine “Maine” as the Wabanaki place that it is and has been for time immemorial.

Kate Stookey of Maine Coast Heritage Trust and Tyler Kidder of the Onion Foundation kicked off participant speeches.

Kate spoke about some of the MCHT’s work as a collaborator and facilitator at the community and grassroots level with the more than 80 land trusts in the place we now call Maine, as part of a larger statewide effort to collectively and individually build relationships and connections with Wabanaki tribes. Kate outlined successes, learning, and challenges with MCHT’s work on all levels–internally and in collaboration. MCHT’s foundation and focus has been building relationships with Wabanaki people. Kate invited us to consider how MCHT and the conservation community share the stories of Wabanaki support and partnership towards building collective awareness as a means for bolstering capacity for Tribal work, priorities, and fundraising for Tribal projects.

I resonated with Tyler’s reckoning with the privilege that enables her access to nature and also the immense health benefits that come from deep connection and relationship with it. Tyler articulated Onion’s organizational intentions and asked for this group’s accountability in the following three realms: transparency in what the organization believes and still needs to learn, commitment to dynamic work that can change and grow, and that the people in the organization lead with their hearts and seek connection with others.

Roger Milliken led perhaps my favorite portion of the day, reminding us that turning around to walk back from 500 years of settler colonialism will be a long journey. Towards this, Roger asked us to let go of judgments and deeply listen to each other responding to the following:

- Something you feel good about, that motivates you or your organization in FirstLight work.

- A resistance in this work that challenges you, internally, in your organization or with others.

I heard several themes:

Positives and motivators

- Change is good but uncomfortable. In spite of this, this work is so important.

- Some people inside our organizations are receptive and supportive. People inside organizations are questioning the status quo.

- Organizations and leaders have already changed the way they do their work.

- Efforts are being made to map where there is interest in land return.

- Wabanaki people inside of organizations are impatient in a good way–pushing the work forward in a positive way.

- Expanding relationships with Wabanaki partners, who inform shifts in conservation paradigms is happening.

- Funding priorities are now focusing on support for Wabanaki people, tribes, and organizations.

- Changing land gift policies is happening.

- There has been increased understanding of the importance and significance of islands to Wabanaki people. Work is being done to create better access to islands.

- We collectively in this room hold immense power and privilege.

Challenges

- Often resistance to the change this work requires comes from Boards.

- The system for protecting land is through a legal process. The concept of land return is outside of a system of legal assurances but rather is based on trust and relationships.

- Funding systems and legal systems for conservation organizations are problematic and run counter to land return unencumbered.

- We are fearful of words and saying the wrong thing. Words can create harm but are also necessary for communicating in an appropriate way.

- The work is hard because we make it hard inside the systems we operate in. It isn’t actually that difficult.

- We are reframing whose opinions we center and how we own the impacts of harm created, even if inadvertent.

- We are redefining our relationships with the natural world and the relationships we teach young people: reciprocity versus a mentality of “this (natural world) is here for me”.

- We are challenged by our egos, desires, training, and socialization that have been steeped in white supremacy and settler colonialism norms.

- We acknowledge the pain and isolation of ceding power

- This work requires us to step off Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum’s moving sidewalk when we are still being asked to achieve the goals that are on it within our work and organization.

- Wabanaki people need to be the ones informing this work.

- We are reframing and correcting the history of place. We are grappling with the question, “Whose legacies do we celebrate?”

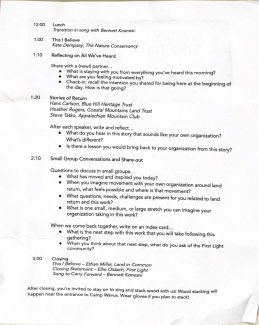

Photo by Peter Forbes

As I struggled to scrawl notes hoping to capture the atmosphere of vulnerability and the richness of what everyone shared, I also noticed the smell of smoked fish wafting into the room. We broke for a lunch that honored Native foods: fiddleheads, smoked alewives and other vegetables. I felt nourished from both the food and from snippets of conversations with friends I haven’t seen enough over the past few years.

After lunch and more group singing, Kate Dempsey of the Nature Conservancy shared the resounding words of John Banks and Penobscot Chief Kirk Francis, “Don’t forget us”. And reminded us of both the need to listen and rebuild trust. Kate said, “Building trusting relationships means we need to give something up”, and acknowledged not everyone has joined this imperative towards Wabanaki land return. The Pine Island return mandated the organization slow down and step back, and while this is hard, this was the only way to do this work.

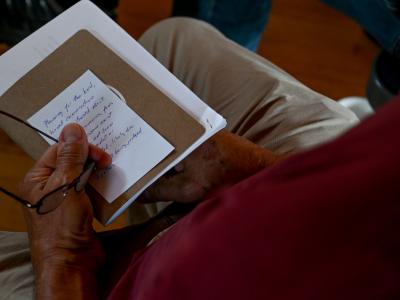

Following Kate’s speech, Ellie invited us to share with each other and reflect on our own in writing: What is staying with you? What are you feeling motivated by? She also asked us to reflect on the intention we had written on notecards earlier that morning.

I reflected on words from Jesse Saffeir that had really rung true for me–that this work is only hard because it is situated within systems of white supremacy–that the actual work itself is not that difficult. And, that we, collectively, have immense power and privilege to wield towards centering Wabanaki sovereignty. I looked around at all of us–Executive Directors, Board members, those with long-standing career expertise, those with proximity to funds, those controlling substantial wealth and more. In taking that in, I felt the weight of our collective power.

Hans Carlson of Blue Hill Heritage Trust, Heather Rogers of Coastal Mountains Land Trust, and Steve Tatko of the Appalachian Mountain Club all shared their “Stories of Return”.

Hans reminded us that the idea of land return encompasses much more than repatriating land to Indigenous people–that the Indigenous concept of rematriation is an important way to frame land return holistically.

Heather talked practically about steps CMLT has been taking, reminding us that seeking additional learning is easy but that making time is the hard part. She talked about strategies the organization is taking and emphasized the need to cultivate Wabanaki relationships and make offerings of resources. I resonated with the concept Heather shared of “mission drift versus mission maturity” as a way of reorienting to how we think about internal organizational change.

In Steve’s story, he acknowledged the inherent flaws of permits, a Western construct, but one AMC has been working with, shifting from being in the gatekeeping role, to a system of permitting given through tribal officers. Steve’s speech also made me reflect on how the Western constructs that are and were built to address the values of care, actually don’t enable us to manifest it, evidencing that some of the most pristine, priceless land is alongside those who live in poverty.

Photo by Peter Forbes

Following these powerful stories, we gathered in small groups and shared what had been moving and inspiring, as well as what felt possible within our organizations. This got us collectively thinking about possibilities. Ellie invited everyone to write down what commitments we are making moving forward. I appreciated this culmination point of the day, and was struck again by how powerful we are as a group.

Some commitments shared included:

- Instilling financial commitments to land return in organizational policies.

- Proposing land transfer policy changes to our boards.

- Bringing together conservation funders to address issues that restrict land return, towards allowing conservation organizations to be more innovative and creative.

- Leaning into the idea that this work can be easy, it’s systems related to colonialism and white supremacy that makes it hard.

- Acknowledging the need to create space for generational trauma and healing.

- Working internally to develop three tracks for conservation: 1) internal conversations about land return. 2) leveling up the organization’s values by reevaluating and restructuring to enable changes and 3) thinking about and practicing land back and repair broadly, including indigenous land but acknowledging other historical harm and ongoing oppression.

Photo by Peter Forbes.

Ethan Miller of Land in Common then spoke a powerful closing. He brought into focus what I also believe: that we must use all of our energy to stop harm being done in the name of colonialism, and simultaneously stand alongside Wabanaki people and nations. We must return power, land, and wealth. This work also matters because it is part of collectively reclaiming our own humanity. “Collectively all of our lives depend on doing this work,” he said and reminded us that the same systems robbing Wabanaki people are also robbing us. Consistent with one of the important themes of the gathering for me–vulnerability–Ethan said, “We cannot do this work unless we make ourselves deeply vulnerable and make our organizations vulnerable” and also that this work can be joyful, healing, and precious. Inherent in this work is the need to rely on each other.

Bennett closed the gathering with a song to carry us forward. We left a sweaty bunch with the smell of alewives on our fingers and drove home in pelting, drenching rain, a lightning show and rumbling thunder. We know great change is happening in the world. There is upset and turbulence related to the oppression of people and Earth. The storm seemed almost a cliche reminder of it. But I need these powerful reminders–both the Gathering and the storm–in order to embrace vulnerability, slow down, listen, focus on people and our relationships, and sing together. Some days the pace of my life barely allows for one minute of this, unless I pick my head up and remind myself that this is actually what the work is. Everyday I need to remind myself to step off that moving sidewalk, turn around, and keep walking 500 years back out.

Photo by Peter Forbes.